Legends of the skies flew into aviation history

Courage and skill in the sky. Ingenuity and engineering prowess on the ground. Determination to prevail and daring to be different.

These attributes apply to five Canadian pioneers – women, men and aircraft who blazed indelible trails in the annals of aviation. All are exemplars of engineering achievement or exploits in the cockpit.

Three individuals and two aircraft are honoured in Canada Post’s Canadians in Flight stamp issue:

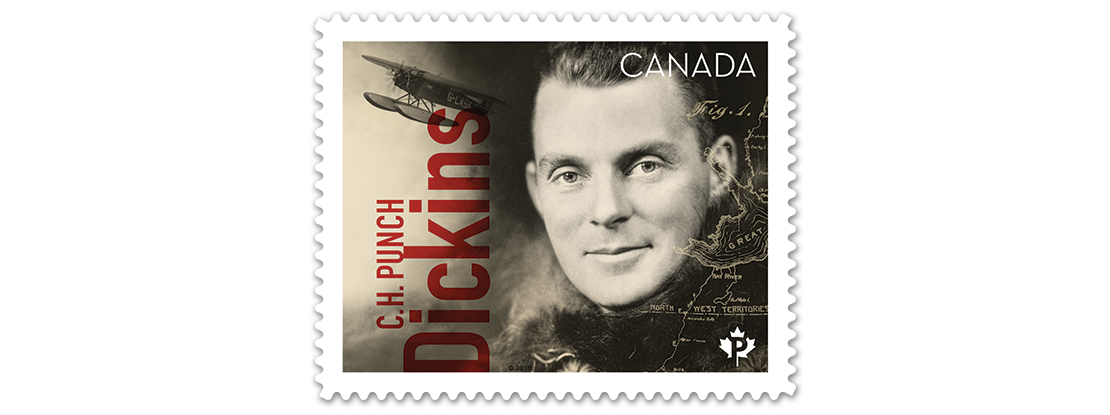

Legendary bush pilot C.H. “Punch” Dickins

Punch Dickins (1899-1995) logged more than 1.6 million kilometres flying over northern Canada.

A young ace decorated for gallantry in the First World War (receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross), Dickins also served on the home front in the Second World War: he managed the schools that trained thousands of Commonwealth aircrew, and oversaw the effort to ferry planes built in North American factories to European fronts.

But Dickins is remembered most for his pioneering flights over vast distances above the wilderness of Canada’s north.

In 1928, he made the first reconnaissance flight across the unmapped Barren Lands of the Northwest Territories – covering more than 6,000 kilometres in 37 hours of flying time. In those days, he flew where no airports existed; he arranged in advance for steamboats to place barrels of aviation fuel along his route. On one flight, he ran out of fuel in the middle of nowhere, landed his floatplane safely, and waited. Along came a steamboat. He asked the crew if he could hitch a lift to his fuel cache. The boatman told him he had aviation fuel on board already – “for some fella named Dickins.”

Luck helped, but far more than luck gave life to the Dickins legend. He was also a consummate outdoorsman, pilot and mechanic. His grandson, John Dickins, of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., marvelled at his abilities.

As a boy of seven or eight in the early 1970s, John flew from Edmonton deep into the N.W.T. wilderness in Punch’s Twin Otter – which had his name painted on the fuselage. During that week-long fishing trip, Punch taught him about flying, weather, mapping, fishing, shore cooking, starting a campfire and survival.

“I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was being taught by arguably one of the best in the entire world,” John recalls. “He had lived all these things for over 70 years. He had mapped without GPS, and he could fish, trap or catch food to survive.”

In 1984, in Victoria, Punch picked up John at the airport for a visit. Punch was 86 years old, and at the wheel of a sparkling, purring 12-cylinder, 5.3-litre, four-carburetor Jaguar E-type Series 3. It looked like it had been driven off the showroom floor that morning. It was actually 13 years old. Punch had done all the maintenance.

“He was meticulous, a brilliant mechanic.”

Dickins was called “Tingmashuk” by the Inuit, which means “birdman.”

Audacious ace William George Barker, VC

A First World War pilot, William George Barker, VC, (1894-1930) remains the most decorated member of the military in the history of Canada and the British Empire.

Barker flew more than 900 combat hours between 1916 and 1918 and is credited with 50 victories over enemy aircraft. Fellow ace Billy Bishop called Barker “the deadliest air fighter who ever lived.” He downed 46 enemy aircraft while flying the same plane – his Sopwith Camel B6313. Historians of Britain’s Royal Air Force called it “the single most successful fighter aircraft” in RAF history. Barker never had a wingman flying with him killed, nor an aircraft he was escorting shot down.

Barker’s deeds earned him numerous honours, including the Victoria Cross, the Distinguished Service Order (twice), the Military Cross (three times) and medals from France and Italy.

He was also something of a rascal – or at least determined to re-enter the fray. After being wounded, he was sent back to England to instruct pilots. Frustrated, he buzzed Piccadilly Circus in his biplane. His superiors got the point – and reassigned him to a combat squadron.

Barker’s grandson Alec Mackenzie of Surrey, B.C., made a pilgrimage to France on October 27, 2018 with two other grandsons of Barker’s. That morning, they all stood near the spot where a gravely wounded Barker had landed his wrecked plane 100 years earlier – to the very day and hour. With his three grandsons was the grandson of the British officer who had pulled Barker out of the wreckage.

“For us, this truly lifted the story from the pages of history,” says Mackenzie.

Despite being outnumbered by a large German formation, Barker had shot down four enemy aircraft before being shot down himself. His feat that morning earned him that Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for valour.

After the war, Barker partnered with Bishop to form one of Canada’s first commercial airlines. In 1919, he became the first Canadian pilot to carry international airmail.

He was killed while flying a plane over the Ottawa River near Rockcliffe, in 1930, aged 35. Some 50,000 spectators watched his state funeral, which was then the largest such attendance in Toronto history.

Elizabeth “Elsie” MacGill: a life of “firsts”

All her life (1905-1980), Elizabeth “Elsie” MacGill broke through barriers.

She was the first woman in Canada to receive a degree in electrical engineering, to hold a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering and to work as a professional aircraft designer. In 1946, she became was the first woman to chair a United Nations aviation technical committee, and played a leading role in creating the international airworthiness regulations for commercial aircraft.

She was also the first woman in the world to design all of the major components of a manufactured aircraft – the Maple Leaf Trainer II.

She was dubbed “Queen of the Hurricanes” in a wartime comic book for her leadership in overseeing design refinements and production of Hawker Hurricanes. The fighter plane was a stalwart workhorse in the Second World War, and especially the Battle of Britain. She was put in charge of the team that retooled a former railway freight car factory in Thunder Bay, Ont., and retrained its hundreds of workers, to make an aircraft with thousands of parts. MacGill also made many of the plane’s components easier to replace if damaged in combat.

A member of the Order of Canada, of Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame and the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame, among other honours, MacGill was a champion of women’s rights – advocating, for example, for paid maternity leave. In 1967, she was appointed to the influential Royal Commission on the Status of Women.

Her accomplishments speak to her intellect, but her response to being told she’d never walk again speaks to her determination. When MacGill contracted polio in her 20s, doctors told her she would spend her life using a wheelchair. She refused to accept that – and taught herself to walk with the help of metal canes.

Later in life, MacGill was caught in a blizzard while driving from Montréal to Ottawa for an important meeting. Her car got stuck in a snow drift. She calmly put the gearshift in drive, climbed out to push with her shoulder, and once it got moving, pulled herself back in “and off she went,” recalls Rohan Solesby, MacGill’s grandson by marriage.

“This is just one small example of her ‘can-do’ attitude,” he says.

The Lazair – one of the best ultralights ever

The Lazair, a twin-engine, high-wing ultralight monoplane, was designed by a modern-day Daedalus.

In Greek mythology, that genius inventor flew on wings woven of feathers and wax.

In this real-life tale, genius inventor is Dale Kramer of Port Colborne, Ont. His Lazair was made from modern aircraft material, and sold like hotcakes to ultralight enthusiasts the world over.

His design is considered one of the best ultralight aircraft ever made.

“Over the years the Lazair has brought many, including me, endless fun and adventure,” says Kramer. “I still fly my Lazair and I never tire of the feelings of freedom and wonder that I experience.”

The young Kramer had abandoned his aerospace studies to pursue his dream of flying solo in an aircraft anyone could build. He designed and built a stable, aerodynamic and truly ground-breaking microlight plane. The 1979 Lazair was powered by two chainsaw motors perched high on the wing’s leading edge. It weighed less than the average pilot.

It cruised along at a lazy speed – about 65 kilometres an hour – which inspired its name. It could take off and land almost anywhere. And anyone with some skill could build their own.

Kramer’s design won awards at air shows around the world. His company went on to sell more than 1,200 Lazair kits between 1979 and 1985 – all made in his hometown.

Kramer, who has been honoured for his outstanding contributions to aeronautics in Canada, still enjoys the calls he gets from former Lazair owners. They usually tell him how much they loved, as he puts it, “flying slow over the treetops with the wind in their faces.”

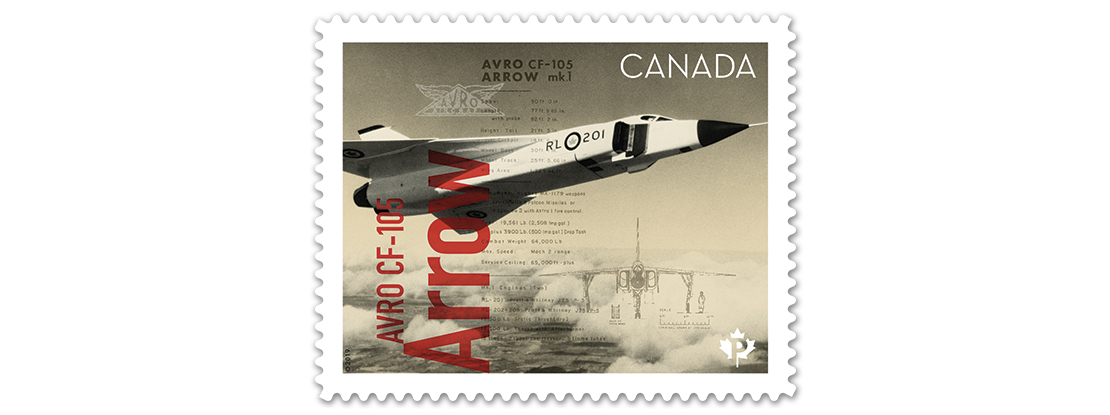

The Avro CF-105 Arrow

Considered one of the greatest technological achievements in Canadian aviation history, this twin-engine, supersonic interceptor could fly at more than twice the speed of sound.

It was designed and developed in Malton near Toronto between 1953 and 1959, at the height of the Cold War, to intercept Soviet bombers. Its engines were lighter and more powerful than any American or British rival plane. It also pioneered a “fly-by-wire” computerized technology, and advanced Delta-shaped wings that were ideal for speed and efficiency at extreme altitude. These are but two of the innovative technologies still in use today.

On March 25, 1958, test pilot Jan Zurakowski flew Arrow RL-201, one of only five Arrows ever built, on a 35-minute flight from Malton Airport (now Toronto Pearson International Airport) that proved its capabilities.

Less than a year later, the program was cancelled, but the Arrow’s legacy of pride and achievement lives on.

These individuals and aircraft are honoured in Canada Post’s Canadians in Flight stamp issue.

Canadians in Flight stamps on sale now